By Jonathan Whitcomb

This is just a preliminary introduction to the basic structure of the Animal Discovery database for the sighting reports. It’s most useful to those who have some background in databases in general and LibreOffice Base in particular.

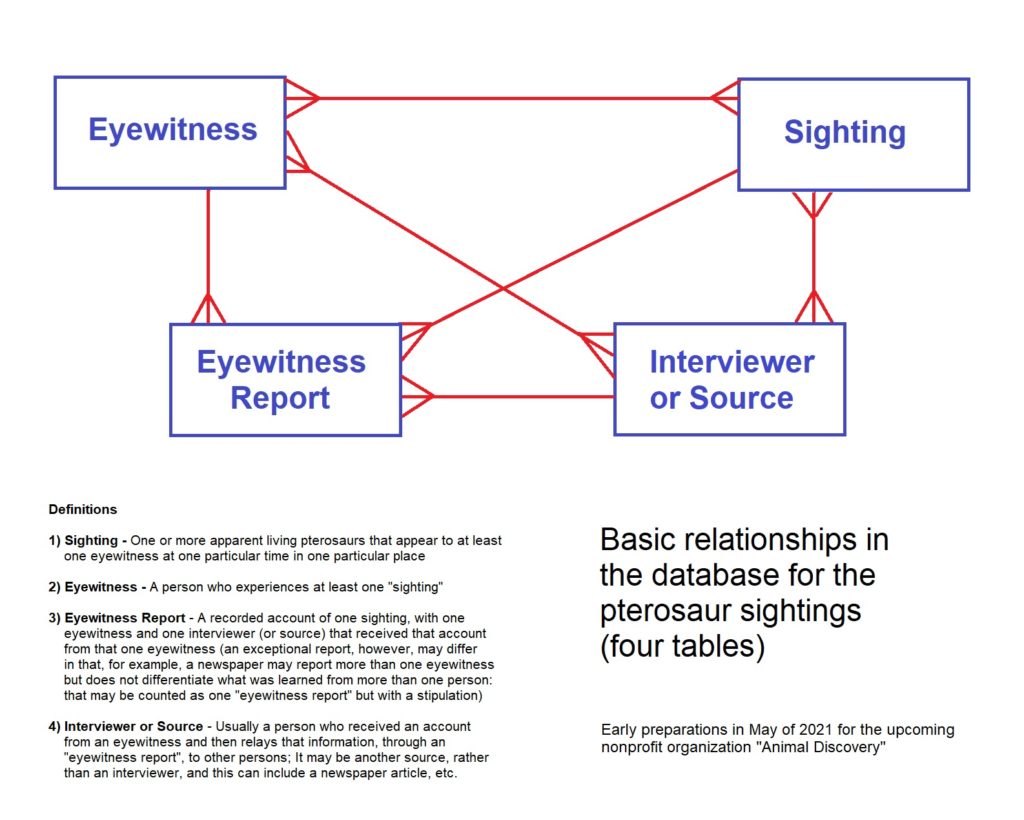

The above shows how four tables are related in the database

“Sighting” (or SI)

First, be aware exactly what is meant by a “sighting” for these records in the database: At least one eyewitness sees an apparent living pterosaur (a.k.a. “pterodactyl” or “flying dragon” or “dinosaur bird”), at one particular time and in one particular place. If an eyewitness sees the animal for a few seconds to the right of some trees, and it flies behind those trees for five seconds or so and then appears on the other side of those trees, it is the SAME sighting. In that situation, don’t get fancy pants.

Now for a simple view of the database table “sighting”: It contains not much more than the place of the sighting, the year of the sighting, and the main eyewitness (first and last name). In other words, this table has very few fields.

Do not confuse “sighting” (SI) with “eyewitness reports” (ER), as defined here. An SI record may have more than one eyewitness and more than one person who interviewed one of those eyewitnesses. An example of this is the sighting west of Finschhafen, New Guinea, in 1944, in which two American soldiers encountered a huge “pterodactyl” that had a long tail. To be technically correct in maintaining details in the database, the SI record needs to connect with two ER records, for one of those two men, Duane Hodgkinson, was interviewed by two persons: me and Garth Guessman. If the other American soldier had reported the encounter, then we would have needed at least one more ER record to connect with that SI record.

Duane Hodgkinson

Another example of how one sighting would need to have two eyewitness reports is this: a couple was taking a walk at night in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles County, California, when they both saw a gigantic flying creature overhead. I interviewed both eyewitnesses, so this SI record would need to connect with two ER records.

“Eyewitness Report” (or ER)

This table has dozens of fields: year of sighting, date, nation and other location information, presence of a long tail (yes or no or null), color description, was a reporting eyewitness in a moving vehicle, approximate time of day, was it cloudy, was it hot, was there a head crest, estimate of wingspan in feet, did it surely have not feathers, did it only probably have feathers, etc.

An ER record connects with only one record in each of the other three principle tables of the database: SI, EYE, and I-S.

Here is the precise definition of the ER table:

It’s a recorded account of one sighting, with one “eyewitness” and one “interviewer or source” (I-S) that received that account from that one eyewitness. (An exceptional report, however, may differ in that, for example, a newspaper may report more than one eyewitness but does not differentiate what was learned from more than one person: That may be counted as one “eyewitness report” but with a stipulation.)

“Eyewitness” (or EYE)

It is simple: a person who has had at least one “sighting”. The fields will be mostly be things like first name, last name, phone number, email, and details about the address.

“Interviewer or Source” (I-S)

Here’s the definition of this table:

An I-S record may be a person who receives accounts from eyewitnesses and then relays that information to other persons or to the general public. Another I-S record can be a newspaper article or comment section under a particular Youtube video, etc. (Be aware that one I-S record may be connected to more than one SI and more than one ER and more than one SI.)

###

The word ropen comes from the Kovai language of Umboi Island in Papua New Guinea, although over the past fourteen years it has become known around the world as a word that refers to any modern flying creature that appears to an eyewitness to be a featherless long-tailed pterosaur . . .

To inform the public about the existence, or potential existence, of apparent modern pterosaurs . . .

.